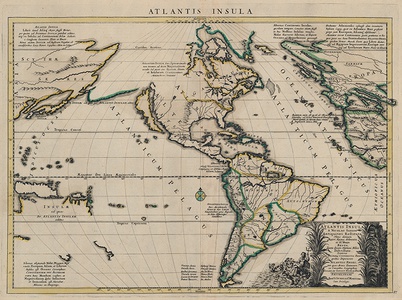

| Method | Copper engraved with early hand colour |

| Artist | Mortier, Pierre |

| Published | Amstelodami. Apud I. Covens et C. Mortier. Cum Privilegio [Amsterdam, c.1720] |

| Dimensions | 405 x 550 mm |

| Notes |

The Atlantean myth transposed upon the Americas, engraved by Pierre Mortier following a design by the great French cartographer Nicolas Sanson. The map shows the American continent at centre, with parts of western Europe and Africa, and Eastern Asia and Australasia. California is shown as an island, Greenland is joined to Canada, a putative Alaskan coast stretches towards Kamchatka, and isolated coasts in the bottom left corner of the map represent parts of northern Australia and Carpentaria, New Zealand, Tasmania, the Solomon Islands, and New Guinea. Because of the projection, the extremities of the map have become exaggeratedly elongated. Japan is shown as a very thin island near a similarly thin Korea, which is, however, shown correctly as a peninsula, while on the western side of the Atlantic, the British Isles, Scandinavia, and the Italian peninsula in particular are almost comedically represented. In the bottom right corner, the lengthy title is flanked by a vignette of Neptune and his retinue. By far the most interesting aspect of the map though is the way in which the classical traditions related to Atlantis have been interpreted for application to the Americas. The first surviving mentions of Atlantis, more correctly the Island of Atlas, are in Plato's dialogues Timaeus and Critias, where the people of Atlantis are described as a formerly great nation that fell from favour with the gods and was plunged into the sea. For Plato's purposes, the island and its expansive empire stood as a philosophical counterpoint to the idealised state of Athens as described in the Republic, and a lesson in hubris. Other ancient authors were divided on the historicity of Atlantis, some seeing it, as Plato did, as a literary device, others, particularly geographers and mythographers, as a real historical island or nation beyond the Pillars of Hercules. Sanson's design for the current map follows much of the classical source tradition. The 'island' of the Americas is divided into ten kingdoms, each ruled by one of the ten sons of the sea god Poseidon. Atlas, his oldest and greatest son, is given pre-eminence. The two great cities of Atlantis, Machimos (Warlike) and Eusebes (Pious), are applied to the two greatest pre-Columbian cities known to Europeans at the time, Mexico City and Cusco. Islands and landmasses beyond the Old World are labelled as parts of the great naval Atlantean empire, and copious notes about the size and scale of the Island draw from various classical traditions. The Hesperides, the blessed isles of Greek mythology, are here identified with the Caribbean, and Iceland is labelled 'Thule.' The myth of Atlantis continued to be a popular literary device throughout late antiquity and the medieval period, and by the sixteenth century had become a common trope in writings about the ideal state, including More's Utopia, and the less well known but equally influential New Atlantis by Bacon. In connection with the Americas, this latter is perhaps the most important literary foundation for the current map. Bacon was intimately involved in the British Crown's intentions for the settlement of North America, with the author contributing a review of the fledging colony of Virginia among other things. His discussions of concepts that now seem familiarly American, like the separation of church and state, the freedoms and liberties of the individual, and the championing of the scientific method, were all laid out in the New Atlantis. Sanson's map was still unissued by the time of his death, so was first engraved and published by his son Guillaume in 1669. Two further derivatives were made, the first by the Seminario Vescovile in Padua in their 1699 Tabulae Geographicae, and the example, as here, engraved by Pierre Mortier around 1705. Full title reads: Atlantis Insula a Nicolao Sanson Antiquitati Restituta. Nunc demum Majori Forma delineata, et in decem Regna, Iuxta decem Neptuni Filios Distributa. Praeterea Insulae, Nostraeq. Continentis Regiones quibus Imperavere Atlanticis Reges, aut quas Armis Tentavere, ex Conatibus Geographicis Gulielmi Sanson Nicolai Filii. Pieter Mortier (1661–1711) was an 18th-century mapmaker and engraver from the Northern Netherlands. Mortier was born in Leiden. According to Houbraken, David van der Plas worked with him on etchings for Bybelsche Tafereelen (Bible stories), published in Amsterdam in 1700. He was the father of Cornelis Mortier (1699-1783), who in partnership with Johannes Covens I (1697-1774) began the map publishing company Covens & Mortier (1721-1866). He travelled to Paris in 1681-1685 and won the privilege in 1690 of publishing maps and atlases by French publishers in Amsterdam. He used this privilege to win a similar set of privileges for printing an "illustrated print bible" in 1700. He died in Amsterdam. Nicholas Sanson (1600 - 1667) was a French engraver and cartographer, and Geographer to Louis XIII and Louis XIV. As well as world maps, he also issued a series of historic maps to accompany popular classical texts like Caesar's Gallic Wars. After his death, he was succeeded by his sons Adrien and Guillaume, who frequently sign their work Sanson fils. Burden 405 (Derivative) Condition: Central vertical fold, as issued. Minor time toning to sheet. Verdigris from old colour on verso. Annotations in old hands in ink and pencil to verso, otherwise blank. |

| Framing | framed |

| Price | £1,250.00 |

| Stock ID | 53432 |